I've vaguely known for a long time that there was some essential problem with the system for horse encumbrance in early D&D (O/AD&D). But I hadn't personally done the accounting to pinpoint where the issue was; I recently went on a deep dive on that point. Big thanks to the folks on the

Wandering DMs Discord server for pointing out the problem in OED and helping me think through this reasonably.

Original D&D

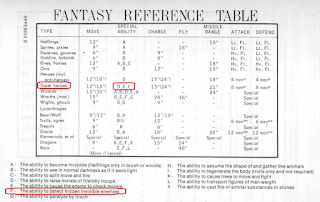

To the side here is the page of encumbrance rules from OD&D (Vol-1, p. 15). Once again I'm struck by the overall

completeness of the Original Dungeons & Dragons rules: whatever its other faults, everything you could possibly need to know about D&D encumbrance is included on this one digest-sized page. This includes: the weight of weapons and armor, helmets and shields, bows and arrows, miscellaneous gear, coins of any type, gems and jewelry, magical treasures, movement categories, container carrying capacities, saddles and barding for horses, and the weight of an average man. Plus a complete example. This compares extremely favorably to what came later: in AD&D, you'd need to look in at least

four separate books, published over

eight years time, to put all the equivalent information back together. (This complication makes it nontrivial to do the desired accounting as I wanted for AD&D, below).

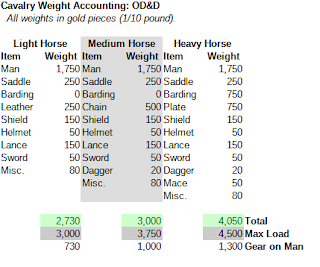

So, here's the accounting for light, medium, and heavy lancer cavalry, under reasonable assumptions, according to the OD&D rules.

Here's some notes & observations on that.

- Horses are only given a single maximum load limit (in the Vol-2 monster entry): by type, 3000, 3750, and 4500 coins. These values are vaguely reasonable: real-world research frequently pegs 30% body weight as the point where horse gait performance starts to experimentally drop off (e.g., Wikipedia: "horses can carry approximately 30% of their weight"). If we take very round estimates for horse weight of 1000-1250-1500 pounds, and compute 30% of those, then we get exactly the load limits shown here.

- The weight of men given, 175 pounds, is roughly equal to the average

weight of men in the U.S. in the era of publication (173.4 pounds, per

NHANES I, 1971-74 from the CDC; compare to S&P's estimate for medieval Swiss men, 71.7 kg = 158.1 pounds).

- The weights for arms & armor seem high, like, around double the weights based on real-world examples (possibly more on that later).

- These rules only give one type each for a saddle, barding, shield, helmet, lance, and one-handed sword, so these are common across each cavalry type.

- Following the listing for bandit men et. al. (in Vol-2), the expectation is that heavy horse are barded, but light and medium horse are not.

- In particular, the barding weight (75 pounds) is reasonable; compare to Wikipedia ("barding, or horse armour, rarely weighed more than 70 pounds"). Several examples at the Met Museum weigh in at around 90 pounds.

Conclusions for OD&D:

- The fully kitted-out cavalryman weighs in nicely within the load limit given for each type of horse (indicated by green highlight in table).

- Moreover, the gear for each type is greater than or equal to the limit for the next lower type -- implying that for medium kit-out you want the medium horse, and for heavy kit-out you really need the heavy horse. (Arguably, you could just barely use a light horse for medium kit; but let's ignore that wrinkle for now.)

- In addition, if we look at the gear on the man alone (perhaps if they have to fight on foot), these weights also synch up perfectly with the encumbrance tiers for men (given as 750-1000-1500 coins). Respectively, each is just barely within the window for light, medium, and heavy loads for men (12-9-6 inch movement tiers).

- Overall -- this is excellent, coherent game system design. All the parts work together to generate the expected & desired results. The numbers are within the ballpark of modern real-world research. It has the sign of someone who paid close attention to both historical details and good wargame design.

Advanced D&D

Now for a different story. First of all, doing a similar accounting for AD&D is a lot more work, because (as noted above), the equivalent information is spread all over at least four different books. To wit:

- The PHB (1977) has melee weapon weights (p. 37), and elsewhere movement thresholds for men (p. 101).

- The DMG (1979) has armor & shield weights (p. 27), and in Appendix O (p. 225), most other weights for miscellaneous gear, bows & arrows, helmets, saddles, etc.

- Container carrying capacities could only be found if you looked in the AD&D Player Character Record Sheets product (1980).

- The specifications for barding weren't given until an article by Gygax in Dragon Magazine #74 (1983), and then reprinted in Unearthed Arcana (1985).

You can take this as a case study of my thesis that there was a lot of key stuff in OD&D that was haphazardly copied or lost in the transition to AD&D, making it a lot more cryptic and mysterious than it needed to be. Anyway, putting it all together we can get the accounting for cavalry weights in AD&D:

Observations here:

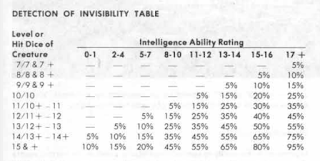

- In the AD&D Monster Manual, horses get two load categories: light (full-speed; approximately equal to the OD&D limits), and heavy (half-speed; about double the light load). That's arguably reasonable.

- The average male human weight of 175 pounds is reiterated in the table on DMG p. 102, so we use that again in our spreadsheet.

- The weight for arms & armor are generally reduced, pulling them more towards real-world scales, as far as I can tell.

- The Advanced D&D ruleset gives distinctions to different types of saddles, barding, shields, helmets, lances, and swords -- so I've indicated the expected selection for each.

- In particular, DMG p. 31 describes medium horsemen as "similar to heavy cavalry", so when necessary I picked the heavier version of the gear (saddle, shield, helmet).

- The AD&D Monster Manual makes no reference to expected barding anywhere in the book (contrast with OD&D above). So are we to assume that light cavalry always use the leather barding, medium chain, and heavy plate, as provided in the equipment list? That would be my best guess of the intent (despite it being ahistorical to my knowledge) -- so that's what I've entered for each type.

- Strangely, Gygax has massively increased the weight of barding to a completely ludicrous level (noted by orange warning lights above). Even the leather barding is more than double the weight of barding in OD&D. Plate barding is more than quintuple the heaviest historical example I could find -- on its own, maxing out the first-tier load limit of the heavy horse. (!)

Conclusions for AD&D:

- The fully-kitted cavalrymen are all significantly over the limit for expected full-speed horse movement. In particular, the heavy horseman is far over the maximum limit for the heavy horse, and cannot move at all by the letter of these rules. The medium horseman is only 3 pounds away from the same thing. (Noted by yellow & red highlights.)

- Apart from the barding issue, looking at the men alone (i.e., off the horse), there is a similar problem. The load limits for average-strength men have been reduced by an order of about a half (35-70-105 pounds in the PHB), and the light & medium men are over the expected limits for the first two categories. (Despite this reduction being maybe real-world reasonable, it outpaced the reduction in arms & armor weight to drop the men into slower categories.)

- Overall -- this design is simply broken. The primary problem is the unwarranted and inexplicable inflation in barding weights (which, again, renders the heavy horseman immobilized). But more generally, the fragmentation of where the encumbrance rules are located (scattered all over many books) is echoed in the design decisions being unsynchronized, and have produced a fundamentally incoherent system.

Further Discussion

Obviously, this is another instance where the Original D&D system runs the table on the later Advanced D&D system. It's really puzzling how the latter system was allowed to get so fragmented, so quickly, as to produce results like this.

I suppose one could argue that the light and medium horse types shouldn't be expected to wear barding -- despite a move-limit table in Dragon #74/Unearthed Arcana showing them in it (a table which doesn't make any sense, because the raw weight has already slowed the horse down more that the table shows for armor max moves). At the very least, you have to observe that plate barding is useless, because it and a heavy horseman are more than any horse can bear.

Of course, a lot of people don't want to use encumbrance rules at all. If you've read this blog before you're likely aware of my argument that scaling the weight units to individual coins was too fine-grained, and juggling all the big numbers is a major part of the headache. So I prefer using a bigger unit like historical stone weights, which (usually) makes the calculations easier to estimate and add up.

Based on our research on real-world horse carrying capacity, I'm confident that the 30% body weight number is a solid value to use before horse speed drops off (see short bibliography below). And aligned with patron feedback, I've become convinced that the 20% body weight number cited in a lot of modern horse-riding articles represents a very conservative rule-of-thumb, trying to be painstakingly humane, with a large safety buffer built in (i.e., not representing medieval workloads). For the OED House Rules we plan to use a round guideline of 1/3 and 2/3 body weight for the light and heavy load thresholds. This represents a revision to this prior article.

Finally, I seem to recall a letter or article in Dragon Magazine that pointed

out the problem with AD&D horse encumbrance, in particular, that a

heavy horseman couldn't move at all. But I can't remember which issue,

and asking around online to date hasn't gotten any answers. Do you know

of such an issue?

Answered: In the comments below, jbeltman found the letter we were looking for -- in Dragon Magazine #118 (February 1987), Forum p. 6, by David Carl Argall (of La Puente, CA). Huge thanks to jbeltman for that!

Bibliography

- Bukhari, Syed SUH, Alan G. McElligott, and Rebecca SV Parkes.

"Quantifying the impact of mounted load carrying on equids: a review." Animals 11.5 (2021): 1333. -- This is a really great, recent review of all the research to date around the issue of horse carrying capacity.

- Matsuura, et. al. . Various articles (2012, 2013, 2016, 2018, etc.) -- Matsuura runs a lab in Japan that studies different horse breeds, and keeps coming up with a number close to 30% body weight for the point where any statistical dropoff in performance can be observed.

- Wickler, S. J., et al. "Effect of load on preferred speed and cost of transport." Journal of Applied Physiology 90.4 (2001): 1548-1551. -- Wickler loaded seven Arabian horses with about 20% body weight burdens, let them walk freely with no rider or lead, and found only about a 5% drop in the speed at which they wanted to walk.

Here's a spreadsheet (ODS) with the tables above if you want to play around with them.